Childhood money lessons can start with ‘Cash or candy?’

Americans have a complicated relationship with money, much of it stemming from what we learned (or didn’t) as children.

In most households, money is a subject every bit as taboo as sex, which is why more than half of Americans reported in a recent study that either no one taught them about money or that they learned how to handle finances on their own.

Parents or guardians were the biggest source of information for children fortunate enough to get basic instruction.

No matter the age of your children or grandchildren, there’s no better time to give your family — and your entire neighborhood – a little money lesson, as it’s Halloween and the money talk flowing freely among youngsters when their question of “Trick or treat?” is greeted with your response of “Cash or candy?”

That’s what I’ve done annually at my house since 2016, blossoming into a fun, fabulous and favorite personal tradition that teaches money, decision-making and more.

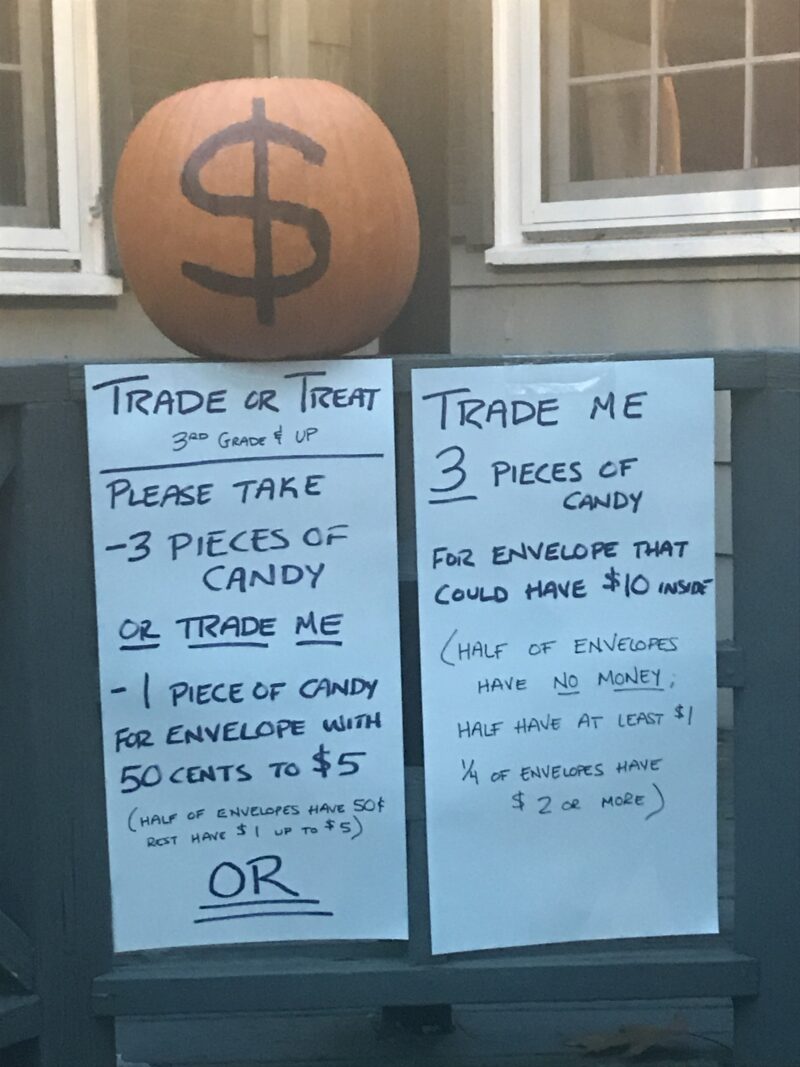

I change up my system every year to keep it interesting for both me and the kids; thus, my methods are over the top.

But whether you use my system or your own, come up with something that challenges the children to think of candy as what it really is to them, a valuable commodity. The fun flows freely from there.

Start by setting a baseline; visiting me in costume “earns” three pieces of fun-sized candy, worth about 37.5 cents total.

Children from the third grade can play my version of “Let’s Make a Deal,” foregoing candy for something else.

In 2016, it was a straight-up either/or choice: take the candy or a coin envelope with at least a quarter in it, and a “jackpot” of $5.

As the only house in the neighborhood handing out cash, it was no surprise that 50 kids took money; two more would have but the envelopes were gone. Just four children chose candy.

In 2017, kids could select an envelope that had at least 25 cents and up to $3, or could trade a piece of candy they had collected to select from envelopes containing 50 cents up to five bucks.

All 48 children who took the money went big; four kids wanted candy.

In 2018, trading in one candy resulted in an envelope with at least 50 cents to a maximum of $4 [half of these “small-money envelopes” held the 50-cent minimum], while trading three candies earned an envelope from a basket where half of the pouches held $1 to $10, but the other half had no money at all.

The total amount of money at stake in the big-money envelopes was just 50 cents more for the small-money envelopes; if all envelopes had been played, kids were choosing roughly the same average result, no matter how much candy they gave me.

In all, 43 kids played for big money -– 23 went home empty-handed — 22 others took the safer choice and 10 stuck with candy.

In 2019, I added a lottery element, the additional option of trading six pieces of candy to play for a $20 jackpot, but every envelope except for the winner and a $10 second prize was empty.

Thirteen kids went lottery, and a boy named Liam won the big jackpot. He will never forget the Halloween when he won 20 bucks.

About 40 children split evenly on the other options; ironically, kids who wanted a guaranteed win but a smaller potential jackpot wound up winning more than the kids who played for something bigger, as roughly half of those players took home nothing.

Covid-19 changed things up in 2020, with the options being a 3-piece candy gift bag, a $1 gift card to the neighborhood ice cream shop, a pool of envelopes with between a quarter and five bucks in it, and the lottery option.

We had a smaller crowd due to virus concerns, but the children who stopped by were split between the money options almost evenly.

The envelopes always include an explanation of the choices and the odds; I ask the kids not to look until they get home, and to discuss the results with parents, asking what mom or dad might have done.

There are lessons about risk and reward, about choices and the value of money.

Last year, the kids took home about $55 in total from me, a bit more than $1.25 per child who chose cash over candy. Giving the ice cream certificate – thereby raising my cost on every taker from 37.5 cents of candy to a buck — was worth it, if only to support a local business.

In the years I have done this, my costs seem to be roughly double what they were when I just offered candy. One benefit is that this limits my exposure to candy, a personal weakness.

It’s worth that money just to hear youngsters talk about money (and sometimes their parents). Moreover, I’m the guy in the house that no longer has little kids playing in the yard or heading to the bus stop; you can’t be scared of the neighborhood old man if he’s giving you money on Halloween.

This year’s twist: Lose the lottery and you can still win, by bringing me your notice of a loss between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day. Wish me a happy holiday with that, and I’ll give you a buck. (I never liked sending kids away empty handed, but I am hoping they see value in being patient in order to collect their reward.)

I have heard 9-year-olds talk about “return on investment,” discuss risks, gambling, the value of money and more. Kids try to calculate every angle — they want to make good choices, they’d like to win – and making them now on something fun will only help them later in life when the stakes are much bigger.

Put your own spin on it and give it a try. It’ll be a treat for you, and if it tricks the kids into learning money lessons, all the better.

#-#-#

Chuck Jaffe is a nationally syndicated financial columnist and the host of “Money Life with Chuck Jaffe.” You can reach him at itschuckjaffe@gmail.com and tune in at moneylifeshow.com.

Copyright, 2021, J Features