Kids like and learn more from cash than Halloween candy

Note: This article was released to newspapers on Nov. 1, 2019

Liam, an eager, blond-haired third-grader, wasn’t playing the odds. He didn’t care about losing five pieces of candy; he couldn’t pull them from his bag fast enough.

“You’ve got to go for the big money,” he excitedly told his friends as he shoved candy at me.

He was the first child on Halloween night to play the candy lottery, the newest twist in my now annual effort to use All Hallows Eve as a means of teaching children about money.

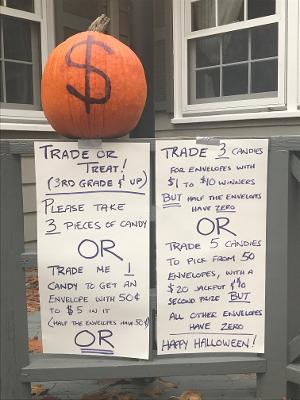

It’s a fun night, filled with conversations about money, value, risk, profits and losses with small children up to teenagers; I change and refine the exercise each year to keep it entertaining. This year, the new gimmick was that kids could trade five pieces of candy for a one-in-50 chance at a $20 jackpot or a $10 second prize.

I never want children to open their “cash or candy” envelopes around me. I’d rather talk money with them than see them win or lose.

“Put them in your candy bag, go have fun, and open them with your parents when you get home,” is my message, because each envelope has a recap of the choices that were available.

But Liam couldn’t wait – that’s not uncommon – and his squeals when he opened the envelope with his dad just seconds after racing away from my front steps made it clear that he had overcome the odds to win the 20 bucks.

Thankfully, Liam’s dad is in the financial-services business. I know he is helping Liam to understand money and its value. Liam won’t win a small jackpot, think you win all the time and become a degenerate gambler.

In fact it was the conversations with the older children – including the dozen teenaged girls who sat down on my front steps to ask questions about their options and about risk and reward – both scared me and made me hopeful for the future.

Scared me because children should understand risk and reward at an early age; hopeful because most of the children were eager to think it out and make a decision they were happy with.

You don’t have to write financial columns the way I do to hear about financial issues for young Americans. From poor savings rates to bad spending habits, lacking financial education in schools and more, the story is that children are unprepared for financial life, leading them to make mistakes that they pay for well into their 30s.

You also don’t have to weigh as much as I do – and wish to weigh less as much as I do – to recognize that the country has an obesity problem even without Halloween candy.

So four years ago, I started my cash-or-candy, trade-or-treat Halloween.

In 2016, children in grades three and higher could choose between three pieces of fun-sized candy or a randomly drawn coin envelope with at least 50 cents up to a $5 jackpot. A year later, it was candy or an envelope with at least 25 cents and up to $3, or trade me one fun-sized piece of candy to upgrade and pick from envelopes containing a minimum of 50 cents up to a $5 grand prize.

It’s no surprise that nearly every child has taken money; candy is abundant on Halloween, while cash is always in short supply.

In 2018, the stakes changed again. Children could choose candy, trade one candy for a sure-winner envelope containing a minimum of 50 cents up to a grand prize of $5, or trade three pieces of candy to pick from envelopes where winners held $1 to $10, but half of the envelopes were empty.

Nearly everyone again took money, but only one-third of the players going for the sure win. (That was the best choice; the average amount per envelope was the same as the big-money game, with no chance of a loss and less candy traded in.)

This year, I added the lottery option: Trade five pieces of candy to pick from 50 envelopes, the two winners and 48 empty losers.

My neighborhood changed demographically this year; prior to this year, I always had more than 50 kids eligible to participate and 25 to 30 too young to participate. This year brought about 50 little ones, and nearly 40 who could play for money.

In all, 13 children went lottery, with only Liam winning. The other options were split evenly. Ironically, the kids who wanted a guaranteed winner and were willing to go for less money wound up winning more than the kids who played for something bigger, as roughly half of those players took home nothing.

Children quickly figured out that one choice was about trying to win big, and another choice was about not losing.

It’s the same thing investors face every day, deciding whether they are more comfortable pursuing smaller, safer gains and how to balance that against pursuing greater rewards but accepting more risk.

The dozen teenagers who sat and chatted with me nearly split evenly. One noted that she went small because “I want to win, I want to take home some money, even if it’s not very much.” Another was quick to play for big money “because I have plenty of candy, but I really want more money.”

Both of those girls said they played for big money a year ago; the girl who wanted the sure win went home with nothing, her friend won a dollar.

“I like trying to figure this out,” said the girl who played it safe. “I wonder what my parents would do, or what they would tell me to do.”

My hope is that she opened her envelope at home, and talked about it with her parents, and that it leads to other money discussions.

Today’s children don’t see parents balancing checkbooks, paying bills or putting money into the bank. They see spending without knowing where the money comes from or what it takes to earn it.

My Halloween experiment won’t change that, but the kids who got $47.50 from me definitely received something more than candy. It was a whole lot of fun and, hopefully, a small start.

One thing is for sure: little Liam will never forget the year he went out for candy and came home with 20 bucks.

#-#-#

Chuck Jaffe is a nationally syndicated financial columnist and the host of “Money Life with Chuck Jaffe.” You can reach him at itschuckjaffe@gmail.com and tune in at moneylifeshow.com.