Cultivating money lessons from the candy bowl

There was a lot of “bad-decision making” at my house this Halloween, and it wasn’t about eating too much candy.

Instead, it was the way the children in my neighborhood responded to my annual effort to turn All Hallows Eve into a lesson about money.

Each year, it’s a fun evening filled by conversations with kids about money, value, risk, profit and loss; I change and refine the exercise every year to keep it entertaining.

The kids’ risk-taking ultimately was my reward, as I gave out less cash this year than last, which was surprising since 2020 – affected by Covid-19 – saw a smaller crowd. That more-conservative group actually took home more of my cash, and therein lies on of the lessons.

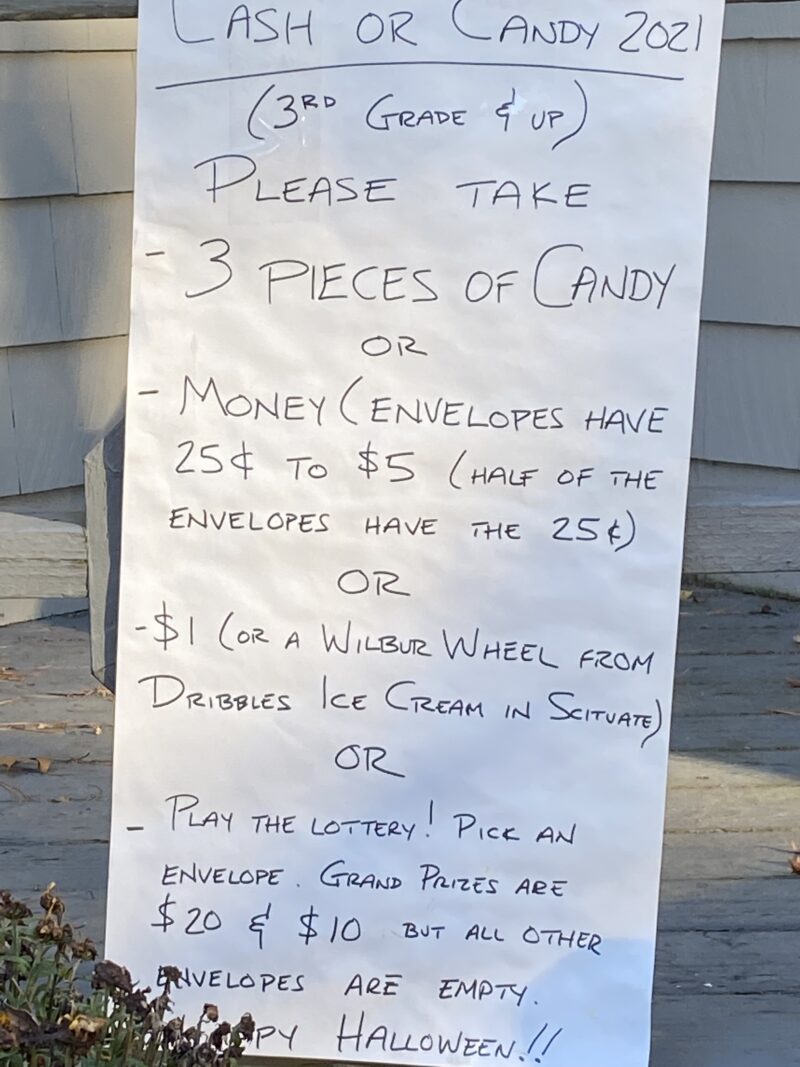

Children in third grade and up had four options when they stopped at my house last Sunday:

Candy: three pieces of fun-sized candy, total value 40 cents.

Cash: envelopes with between 25 cents and $5. Half of the 50 envelopes held the minimum, but the total prize pool was just nearly $60, making the average prize just under $1.20.

Ice cream: A gift certificate to Dribbles – a terrific shop that’s an easy walk or bike ride from the neighborhood – for $1 or a “Wilbur Wheel,” the shop’s signature big, round ice cream sandwich, which costs roughly $1.35 tax included.

The lottery: 50 envelopes, where the jackpots were $20 and $10, but losers got nothing. The prize pool of $30 made the average per envelope – and thus the expected return per play — 60 cents.

Every envelope includes an explanation of the choices and the odds; I ask the kids not to look until they get home, but hope they’ll consider their selection – and how it might have turned out differently – when the excitement of candy-rustling is done.

This year, the twist was that the losing lottery tickets included a note saying the ticket can be redeemed for $1 if the child brings it back and exchanges holiday greetings between Thanksgiving and Christmas.

If the youngsters know the value of a buck, they’ll be back in droves, because 42 kids played the lottery. Someone won the $20, but the $10 wasn’t claimed (meaning the cost of the lottery to me was $20).

Cash players didn’t fare much better; seven children chose that option, and while one took home the $5 top prize, the rest all won a quarter.

Not being able to have follow-up discussions here is unfortunate, because the kids experienced something they’re likely to see as adults: the average win from the cash envelopes was just over 90 cents, which looks great when you consider that each child was “investing” the 40-cent value of the candy.

In reality, however, most cash-selectors suffered a loss, turning 40 cents of candy into just a quarter’s worth of money. The jackpot winner skewed the average.

This year, just one child went for the ice cream, which actually was the best deal based on the value of the ice cream sandwich. It was a guaranteed win, worth three times more than the candy.

Lotteries, of course, are widely considered the epitome of bad financial decisions, drawing no argument from me, but I can’t say that I wouldn’t have pursued the big money had these choices been offered me during my childhood.

Moreover, this lottery had another lesson, one which suggests that the choice those kids made wasn’t so bad. After all, the candy was worth 40 cents, but the average lottery envelope payout was more.

No, the children weren’t thinking of the “expected value” per person, nor truly balancing risk and reward – though the cash selectors either lost the lottery last year or simply wanted to make sure they actually got something from every house they visited – but clearly they grasp those concepts at early ages, and the sooner they are taught them, the better.

There’s myriad proof that Americans have problems ranging from poor savings rates to bad spending habits, and that the problems are particularly prevalent in young adults, who never learned these lessons in school and who are unprepared for leading their financial life, often leading to mistakes that they pay for well into their 30s.

Financial lives are a series of decisions and compromises with consequences. We trade money for goods, services, time, ease/convenience and more; money gives us options.

That’s what the children were learning on Halloween. They “got paid” for showing up, and then got to decide the best use of their capital.

No matter their costume, these little monsters and unicorns and superheroes recognized that one choice was about trying to win big, another choice was about not losing, and a third choice was about maximizing buying power.

It’s the same things consumers face daily in their spending choices, and that investors come up against in deciding whether to pursue smaller, safer gains and how to balance that against pursuing greater rewards but more potential risk.

My hope is that the children and their parents discuss “cash or candy” and that the moms and dads say what they would do, but also relate the situation to other transactions that they make and that the kids see, in places like the grocery store.

Kids today don’t see parents balancing checkbooks, paying bills or putting money into the bank. They see spending without knowing where the money comes from or what it takes to earn it.

That gets worse as society becomes more cashless, because children think credit cards – or apps on a phone – pay for everything without recognizing how the bills actually get paid.

My Halloween experiment won’t change that, but I figure that every lesson we give future generations about handling money will pay dividends, literally and figuratively, down the line.

Now I will wait to see if any of those lottery losers cash in on their second chance during the holidays. I have low expectations, but high hopes; in my experience, that’s the best way to approach teaching children about money.

#-#-#

Chuck Jaffe is a nationally syndicated financial columnist and the host of “Money Life with Chuck Jaffe.” You can reach him at itschuckjaffe@gmail.com and tune in at moneylifeshow.com.

Copyright, 2021, J Features